WARREN MUNDINE

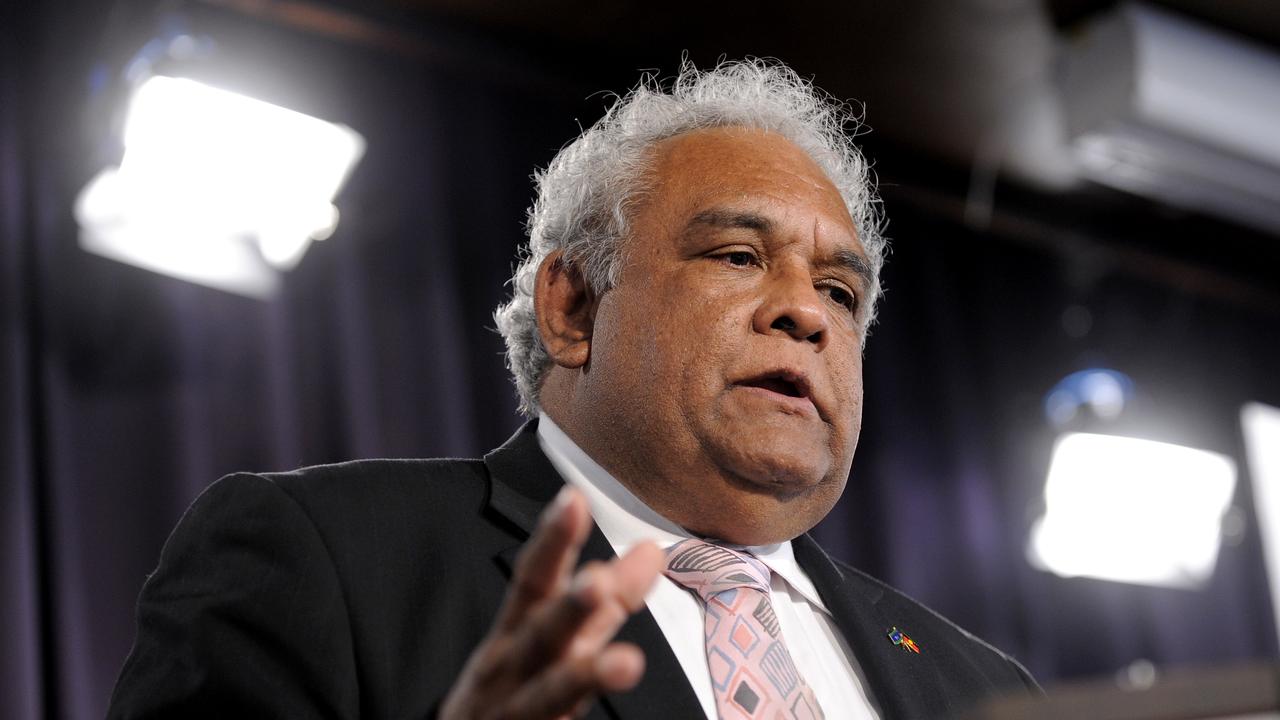

Former aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander social justice commissioner Tom Calma speaking at the National Press Club in 2009

This year Australians will be asked to vote on the most significant change to our system of government since Federation – a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to parliament.

It’s the voice to everyone on everything that will expose every government decision and policy to delay and/or judicial challenge and influence the lives of not just Aboriginal people, but all Australians. Before Australians vote whether to up-end our democratic system, we should understand the nature of the beast. Although he won’t discuss the details, Anthony Albanese intends to implement the 2021 Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Report to the Australian government by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton.

Marcia langton speaks at a key forumduring the Garma festivalat Gulkuls in East Arnhem in July 2022

The report is 270 pages long and stands almost 3cm high on my desk. Because the concept is so complicated it takes many, many words to explain it. It’s so impenetrable, I know highly educated people who’ve struggled to get through it.

Yet it’s this document Albanese has told people to read if they want to know how the voice will work. He seems to have stopped this lately – perhaps he finally looked at it himself and thought twice about encouraging anyone else near it. It’s dense, complex, padded with bureaucratese and hard to decipher. An abomination is a better word.

It’s entirely unsuitable to inform ordinary Australians about such a fundamental change to our democracy and system of government. The report introduces the voice concept as “an urgent solution to the ongoing predicament of Indigenous Australians” with “a robust and feasible means of producing outcomes”. Nowhere in this report are these desirable outcomes described, in any detail or by reference whatsoever.

The report assumes Indigenous people want “a greater say on the laws, policies and programs that affect our lives” and that “non-Indigenous Australians support that call”. What laws? What policies and programs? I can’t think of any that treat Aboriginal people unfairly or were designed without extensive consultation with Indigenous people. The opposite. And there’s no indication of how this will alleviate Aboriginal disadvantage.

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine with indigenous leaders in Canberra. Picture Sarah Ison

The report claims Indigenous people have been calling for a national-level mechanism to have a greater say in Australian government laws, policies and decisions. Really? I think this call comes from a small minority of Aboriginal people from community organisations and academia who already advise government and have been amply funded over years to deliver improvements with little to show for it. Those groups will become the iceberg to the voice’s tip in a complex local, regional and national apparatus.

It’s the responsibility of the Australian parliament to legislate and of public servants to develop and implement policy at relevant ministers’ direction. And within that existing framework, we’ve had a huge increase in Indigenous participation over recent decades. Indigenous Australians are now a significant minority in the federal parliament, above parity.

Indigenous communities, organisations and individuals enjoy a close relationship with local members and a formal, integrated role in advising relevant ministers. Importantly, governments remain the largest employers of Indigenous people and these Indigenous public servants are right now administering the very policies and programs that impact Indigenous communities.

Indigenous people already have a voice, many voices. The report ignores the real gains made in incorporating Indigenous people into the democratic political process that serves all Australians well. The report has so many assumptions, but so little real data.

Firstly, it’s built on the assumption that having Aboriginal people speaking to parliament and government and having their say on legislation and policy will somehow address the “ongoing predicament” of Indigenous Australians. I can’t see this happening at all.

There’s also an assumption that this ongoing predicament will somehow be solved by the workings of government, when it is government policy and programs that figure most prominently in Aboriginal peoples’ lives already. The report never considers that may, in fact, be the root of the problem.

| Former shadow minister for Indigenous Australians Julian Leeser reveals the view in the Liberal party room on the… Indigenous Voice to Parliament was “overwhelming”. Mr Leeser said Opposition leader Peter Dutton came to the Voice debate with an “open mind”. “……… |

It’s evident, in these pages, that the voice process will create chaos and is likely to be unmanageable. How many different Indigenous voices will be heard on any particular legislation, decision or policy? There will be conflicting voices within “the voice” and competing agendas. Will Bills have to be drafted and re-drafted in response to the concerns of the voice? Will Ministerial decisions and policies need a voice sign off. And what if there is a dissenting or minority position within the voice?

It’s evident, in these pages, that the voice process will create chaos and is likely to be unmanageable. How many different Indigenous voices will be heard on any particular legislation, decision or policy? There will be conflicting voices within “the voice” and competing agendas. Will Bills have to be drafted and re-drafted in response to the concerns of the voice? Will Ministerial decisions and policies need a voice sign off. And what if there is a dissenting or minority position within the voice?

Blackfellas aren’t all the same. We can’t speak for each other’s countries. And even within our own country, we don’t always see eye-to-eye. No one expects this of non-Aboriginal people. Australia’s system of government has a process for reaching decisions in a large, diverse society, built on nearly a thousand years of precedent and tradition in the Westminster system. There’s no proposed process for decision-making in the report.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton says he is driven by what is in Australia’s “best interest” and he does not believe… the Canberra Voice to Parliament is in that interest. “For me … I’m driven by what is in our country’s best interest …

The voice is predicated on an assumption of wholesale failure and crisis in Aboriginal communities. It’s true some communities are in crisis, but the suggestion a voice could have prevented problems like those we’ve seen recently in Alice Springs is just plain wrong.

A national voice couldn’t respond adequately even in a preventive manner. And, fundamentally, those problems stem from too many Aboriginal people not participating in the real economy. Being so tied to the public purse, the voice won’t have the first clue how to tackle that.

The voice as articulated by the Calma-Langton report is fatally flawed: flawed in its claim this is what Aboriginal people want, flawed in its proposed structure and flawed in its approach to representation.

Warren Mundine is a businessman and advocate for Indigenous economic participation. Research by Vicki Grieves Williams, academic, historian and Warraimaay woman, also contributed to this article.